It’s safe to say 2020 isn’t ‘back to school’ in the normal sense. With the arrival of fall, higher education students and institutions are faced with uncertainty around the availability of affordable housing and adapting housing facilities to current panademic safety measures.

—Marc Tessier-Lavigne, Stanford University President“The highly communal nature of our undergraduate residential and dining spaces makes them fundamentally incompatible with the concept of social distancing.”

So what does this mean for the future of student housing?

We sat down (virtually, of course) with Pauline Thimm, an Associate in our Vancouver studio, for a discussion of key issues surrounding housing at the campus level, as well as a case study of the nano suites—140 sq ft independent living spaces—deployed at the University of British Columbia (UBC) campus in Vancouver, BC.

Pauline has led and been involved in post-secondary projects of various scales across North America, from programming and planning to renovation, rehabilitation, and new construction. She has worked with institutions such as Simon Fraser University, UBC, the Radcliffe Institute at Harvard University, Dartmouth College, MIT, and Stanford.

Starting from a place of uncertainty, how do we approach student housing during a pandemic?

The pandemic has triggered a seismic shift in the education sector in a matter of months that has required a rethinking of the landscape of higher education. It’s made us ask the question: What is the value of the physical campus? How can the design of the campus and its buildings shape a positive and welcoming student experience while providing an ability to meet health and safety concerns due to unanticipated events such as COVID-19?

More than ever before, higher education requires flexible design solutions that can be adapted to the uncertainty we are currently facing – while supporting a rich and meaningful student experience. It’s important considering what we know about the relationship between student experience, student mental health and academic performance.

Three factors come into play when considering flexible student housing design.

First, a clear understanding who the housing is for. What are the specific needs of the students using the housing? Whether they are undergraduate or older mature students, their needs are often distinct, but are also evolving. The increased emphasis on the student experience and the current need to accommodate social distancing requires us to re-evaluate ideas of social connection and community, for instance by expanding our user engagement sessions early in the design process, and by adapting design considerations to consider new ways of supporting campus community at a variety of scales.

Second is the housing site within the campus. What are the opportunities and constraints? How can the introduction of new student housing contribute to a strengthened public realm and a lively and dynamic urban environment?

Lastly, what are the strategic goals of the higher education institution and how can the design of student housing support their aspirations? While we don’t know what the future holds in a pre- / post-vaccine world, designing for the highest level of efficiency and flexibility allows for future needs to be considered even if they are yet to be defined.

Tell us about the Exchange Residence and UBC Bus Exchange project, and the innovative nano suites that were created.

Like many urban campuses, UBC’s Vancouver campus was, and still is, facing densification pressures and a student-housing affordability crisis. They wanted to build more student beds, while TransLink, the regional transit authority, had a mandate to deliver a new bus exchange – both were running into space constraints on campus. The team came up with an innovative solution to the problem of sharing the gateway site: build up, rather than out – resulting in an unprecedented vertically-integrated design solution that combines the region’s largest bus exchange and layover at grade with student housing “floating” 3 stories above it above it.

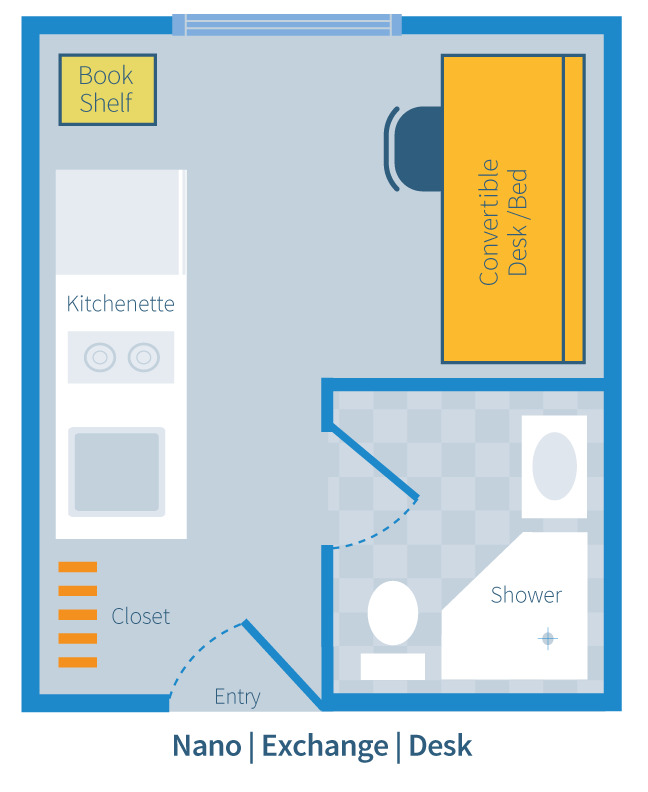

The result was a new 650-bed student residence, which includes 71 of the innovative “nano” micro-suites, being built on a podium above a bus exchange.

The team’s drive to innovate the nano suite was fuelled by a keen understanding of UBC’s ongoing demand for efficient and affordable student housing options – we knew that any opportunity to squeeze more beds on site within the approved building envelope would be of interest.

Developed in close consultation with the students and stakeholders, the suites contain the essential elements for student living in a tiny footprint, including a specialized space-saving Murphy bed that folds up into a desk.

This is a great example of flexible design, and delivers on all three factors listed above.

1) User-oriented: the nano suite caters to undergraduate students who need affordablet private living space close to campus. The nano suite occupants can access generous amenity spaces within the building, and are close to transit, groceries, etc. Being integrated into a mixed-use environment, the Exchange residences offer all the support needed for a successful undergraduate environment – and more!

2) Site: The UBC site created an opportunity to build housing and transit in one place, addressing two important factors in the UBC campus experience.

3) Client needs: UBC was able to gain efficiencies by providing more beds in a similar footprint. There is a shortage of affordable housing on campus and nano suites allow institutions to maximize bed counts and provide a compact way to deliver a solitary living environment. This is paradigm shift in land use, where no one gets the short end of the stick.